In Episode 2: Growing Our Education, we talked a bit about our favorite classes. The specific subtopics of importance in the turfgrass curricula include diseases, soils, turfgrass plant nutrition, irrigation, insects, and last, but certainly not least, turfgrass identification.

While our goal for this podcast was to be geared more toward turfgrass professionals, we recognize that our friends, families, and hey, potential turfgrass professionals, might listen along. Here are a few educational tidbits you can share as fun facts the next time you’re admiring your neighbor’s lawn.

Let’s Get Grassy

There are many different species of grasses, but to break it down, let’s talk about warm versus cool-season species. Cool-season grasses are going to be found in more northern areas where temperatures consistently get below or around 32 degrees F or 0 degrees C for an extended period. These species are what you might find in your backyard in places north of the transition zone- tall fescue, perennial ryegrass, and yes, the villainized water-loving Kentucky bluegrass. Whatever you might find in your home lawn, chances are this species is probably growing in the rough at the local golf course. (The rough being the tall grass areas that are maintained for play, but are not tees, fairways, or greens.)

Warm-season turfgrasses are a whole other beast. If you’re in the southeast, your lawn is probably St. Augustine and you probably hate walking on it barefoot. In the southwest, if you have grass, it could be some zoysia, bermuda, kikuyu or even St. Aug depending on your water regulations. Warm-season grasses are not as delicate as the cool-season species. You can spill fuel on them and they’ll grow out of that burn in less than two weeks at the right time of the year. Cool season species? You’ll be looking at those splash marks for weeks- maybe even a month. Cool season does not grow out of the burn from fuel. Typically it dies, but that depends on the amount spilled.

With me so far? Let’s talk about the species we maintain on a golf course.

Creeping Bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera)

Creeping Bentgrass is a cool-season species that as the name entails, creeps. Instead of being a grass that grows tall and upright at all times, bentgrass can be maintained at heights under a tenth of an inch. Think about that next time you see golf on the TV- those greens they’re putting on are less than .01″ of a plant- Miniscule. It’s hard to see just one plant while you’re standing on a green, but that’s the point. A smooth, even, firm surface perfect for ball roll. That’s golf. Bentgrass is one of the most popular species to be maintained at greens height simply because it’s reliable and plays more preferably than bermudagrass. Depending on the climate, bentgrass can feel like stepping on a sponge. You will sink in, and you will dislike the way your ball plays in areas like this. In other places, bentgrass is god and it would be heretic to describe it as anything but.

Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon)

Bermudagrass is a warm-season species that can grow as wild-type or the hybrid variety that can be maintained at much lower heights. Wild-type bermuda grows tall and wild- the above is a picture I took where the succulents below have been overtaken by wild bermuda. The hybrid variety has been cultivated to grow much more densely and creepingly. Bermuda naturally has the rhizomatous (growing outwardly through the roots) growth habit, the hybrid cultivation has allowed that bermudagrass to grow and be maintained much more similarly to bentgrass.

Annual Bluegrass (Poa annua) commonly referred to simply as “Poa”

Poa annua is one of those things where you either love it or you hate it, but everyone has an opinion on it. Due to its annuality, this species of grass ebbs and flows throughout the year. While the varieties we see now are much less annual than they used to be, poa is know more as a weed than as the goal species on a golf course. Poa patches on greens are the first areas to wilt and become sunken at the first signs of heat, some diseases, and insects. Naturally, this makes poa not an ideal pick for your golf green… Unless you live in an area where poa can thrive. Typically in humid climates that stay under 75 degrees Fahrenheit, poa can thrive sometimes better than bentgrass. These are situations in which a turfgrass manager might cater toward a program where the poa is maintained as the ideal species- the one we want to grow there.

A truly informative read for anyone looking to learn more about poa can be found here. I worked very briefly for Dr. Huff at Penn State where he was working on some different poa projects in hopes of one day going commercial. At this current time, there is no poa seed available on the market.

Annual bluegrass is a prolific grower germinating twice a year, every year. When you see lime-green patches of turf in the spring and fall, look for seedheads. If you see seedheads that have tiny green flowers alternating down the panicle shape you’ve identified your first turfgrass. Good for you!

There are so many different species of turfgrasses that we could dive into. Hopefully, this quick guide can break down what species is most likely growing around you, while also giving you a little insight into the game of golf.

Bugging Out

There are many different insect pests to turfgrass, but the ones mentioned in this episode were mole crickets, white grubs, and briefly annual bluegrass weevil.

Mole Crickets come in a variety of different looks but they all generally have almost goofy-looking front legs- tarsi- and 2 sets of legs you would see on a regular cricket. These bad boys dig tunnels underneath the surface of the grass and eat at the roots. The damage from the feeding can seriously injure and eventually kill the plant, and the damage from the tunneling can cause the plant to dry out also leading to death. Tough stuff, but at least they’re cute!

White Grubs are the larval stage of many types of beetles. Different larval stages (AKA instars) can be determined by the size of the grub at the time of year you’re looking at it. Different species can be identified through their raster patterns (AKA what shape surrounds their butt slit). Some of the common beetle pests to turfgrass are also ones you might find at home- the Japanese Beetle being the most noticeable.

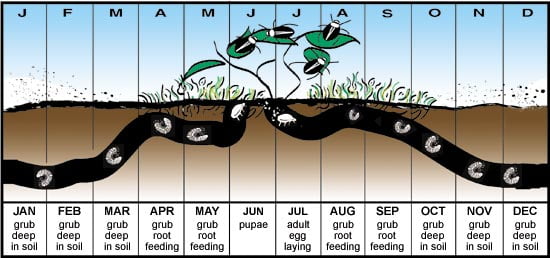

This chart was taken from Wright’s Feeds n Needs’ website (love the name. Also they’re located in Blackstock, Ontario if anyone needs them). What it shows is when to expect grub damage (the times when they’re root feeding) and when to expect adults. Sometimes the adult can be more of the pest than the grub, but since we’re dealing with root feeders that’s not as common as in other situations.

Annual Bluegrass Weevil is a small weevil pest found in the Northeastern United States and Ontario that is slowly beginning its journey to everywhere else. If you’re thinking, ‘Wait didn’t you say before annual bluegrass is a weed? Who cares if it’s out here taking out that poa!” I like the way you’re thinking, but for those who choose to manage poa, these weevils are the last thing you want to see. They prefer short-mown turf near woods where they can feed as soon as they come out of their overwintering. These guys are pesky crown feeders- meaning they chew on essentially the “brain” of the operations. If the crown of a turfgrass plant is injured, death can be imminent depending on the damage. ABW has also gained quite a bit of chemical resistance making them hard to kill in places where the same chemicals were sprayed over and over again- Long Island, NY.

Now that you’re an expert, feel free to share all of the fun information you’ve gained from your turfgrass friends here at On Our Turf! Let us know if you have any questions and we can help guide you in the right direction.